EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege” Oregon legislator and local dentist. Representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 7/14/25

EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege” Oregon legislator and local dentist. Representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 7/14/25

By State Representative Cyrus Javadi

Why the Republic Depends on Showing Up, Even When You’re Losing

In politics, there are sacred cows (and, no those are not the same cows who make the delicious cheese and ice cream you enjoy from my district). Doesn’t matter which team you’re on. Taxes. Abortion. Guns. LGBTQ rights. And, feel free to add Social Security, climate change, election integrity, or whatever today’s algorithm says will ruin America by Tuesday.

And when those issues come up, and they always do, the base starts beating the war drums.

But instead of sacrificing an unlucky virgin to the gods for political victory, the modern ritual is simpler: demand a walkout.

Stop showing up. Deny quorum. Make it so the other team can’t play.

In Oregon (and many other states), we have rules. Some are constitutional, some we make ourselves. You need 31 votes to pass a bill in the House, 16 in the Senate. If it’s a tax, bump that up to 36 and 18. But none of that matters unless quorum is met—40 members in the House, 20 in the Senate.

No quorum? No vote. No accountability.

So when a hot-button issue pops up, say, guns or taxes, the minority party can kill the bill just by not being there. And the base knows it. So they demand it. Walk out, or get primaried. Walk out, or you’re a traitor. RINO. Sellout. Coward. The metaphorical gun goes to the legislator’s head. And, some flinch.

It’s happened before. It happened this session. We knew it would.

When it did, the inboxes lit up. ALL CAPS, no punctuation, name-calling, threats. All saying the same thing: walk out, or else.

Some legislators did. Others didn’t.

So why is it that doing your job—reading bills, showing up, voting—can get you branded a traitor? Let’s talk about why the question even exists, why you should care, and why James Madison could see it coming from a mile away.

The Real Threat is Us

What he saw, clearly, long before cable news or fundraising blasts, was that the real threat to liberty wouldn’t come from a king or a foreign army. It would come from us.

In his time, the country was already fracturing. States were passing laws to punish political opponents. Local factions were hijacking legislatures to cancel debts, favor insiders, and crush dissent. Shays’ Rebellion had just shaken Massachusetts. And under the Articles of Confederation, Congress could barely function. There were no parties yet, but the tribes had already formed.

What Madison feared was the moment when people would stop believing in the process. When passion would override principle. When losing a vote would be treated as proof that the system was illegitimate, and not just as proof that you lost.

His answer wasn’t to suppress factions. That was impossible. No, his answer was to build a structure strong enough to withstand them. A republic big enough and complex enough that no one group could seize total control. One that required participation. One where you had to argue, persuade; and, yes, sometimes lose, and come back again.

Because in Madison’s world, liberty didn’t live in protest. It lived in process. It was protected not by walking out, but by staying in.

He knew that once you start treating the rules as optional, once you decide that your team’s cause justifies breaking quorum, blowing things up, or bypassing debate, what you’re protecting isn’t liberty. It’s power.

Exit Stage Right (or Left)

Now, let’s get something straight: a legislative walkout isn’t civil disobedience.

It’s not John Lewis walking across a bridge for voting rights. It’s not Rosa Parks staying seated.

It’s a politician… not showing up to work.

And yet, we’ve managed to elevate this tactic to near-mythic status in some circles. As if abandoning your post is an act of principle. As if refusing to vote is somehow braver than losing one.

But here’s the truth: walking out isn’t resistance. It’s resignation.

It’s the political equivalent of flipping the Monopoly board when you land on someone else’s hotel. It feels powerful, for a moment. But it doesn’t solve anything. And it doesn’t build anything.

Because in a republic, the real work isn’t theatrical. It’s procedural.

It’s slow. It’s frustrating. It involves reading boring amendments, negotiating edits you don’t love, and showing up for votes you might lose. Those are features, not bugs.

And, that’s the job. The job is governing, not winning. And the moment we decide that job only matters when we’re winning, we’ve stopped governing, and started cosplaying.

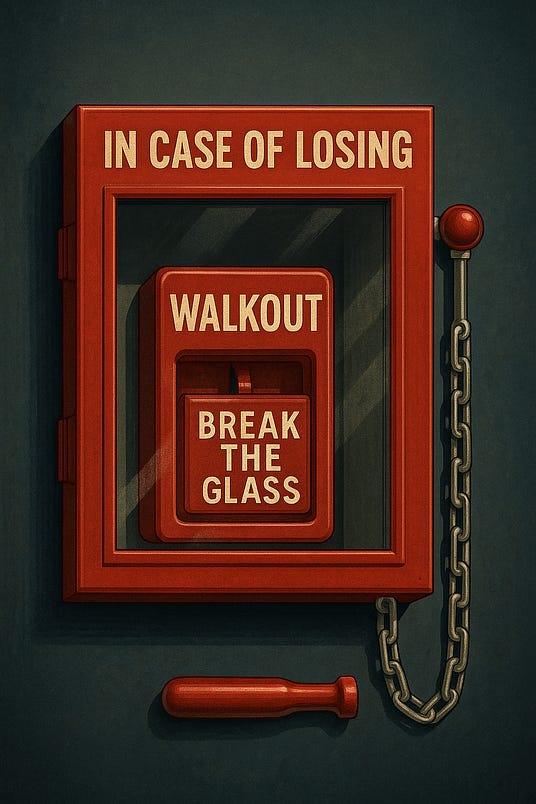

In Case of Losing, Break Everything

The problem with walkouts isn’t just that they’re dramatic. It’s that they chip away at the expectation that the system will function at all.

Once you start normalizing quorum denial as a political strategy, everything becomes conditional.

Votes don’t matter unless your side wins. Rules don’t apply unless they help your cause. Participation becomes performative, just another box to check before launching the outrage cycle.

And before long, it’s not just the other side you don’t trust, it’s the process itself.

That’s when things really start to rot.

Because when voters stop believing the system works, they don’t just vote for different people. They disengage. They get cynical. Or they pick the loudest voice who promises to break everything. And then the whole thing spirals: more walkouts, more stunts, more uncertainty, less accountability.

That’s how we lose a republic. Not in a single collapse, but in a thousand little exits.

When Losing Feels Like an Emergency

Now, let’s be honest: if Democrats had walked out during, say, a vote on a tax cut or a gun rights expansion, Republicans would have screamed bloody murder. “Quitters!” “Cowards!” “Enemies of democracy!” And they wouldn’t have been entirely wrong.

But here’s the thing, neither side is immune. When you’re in the minority, the temptation to “break the glass in case of emergency” is strong. And every year, more and more issues get labeled an emergency. Not because they threaten lives or liberty, but because they threaten someone’s sense of control.

The definition of an emergency has started to shift. It’s no longer “this will do irreversible harm.”

It’s “I don’t like where this is headed.”

It’s “this feels wrong.”

It’s “my base won’t tolerate this.”

It’s “I don’t want this vote on my record.”

And so the glass keeps breaking. Over and over.

We Didn’t Start the Fire, But We’re Here to Fight It

And here’s the real danger: when walkouts become the norm, everything becomes a hostage situation. Real people suffer. Hospitals lose funding. Businesses don’t know if they should invest. Counties can’t plan. And every delay becomes an excuse for more dysfunction.

What’s worse, some of the same people who walk out will later campaign as the firefighters, promising to fix the blaze they helped set.

They think voters won’t notice. And maybe some don’t. But I think most Oregonians are paying closer attention than that.

They want predictability. They want accountability.

They want adults in the room—people who show up, tell the truth, and do the job.

A Better Way to Fight

I don’t blame the base for being angry. I’ve seen the same headlines. I’ve felt the same frustration. It’s easy to believe that walking out is a righteous stand when the issue feels personal or the vote feels rigged. But here’s the hard truth: walkouts don’t stop bad policy, they just weaken the system that’s supposed to protect us from it.

If you want lawmakers who will fight for your values, ask them to show up. To vote. To argue. To stay. Because real strength isn’t storming out of the room. It’s staying in it when it would be easier not to.

Personally, I believe, if you hate a bill, vote no. If you think the process was flawed, raise a point of order. Talk to the press. Hold a town hall back home and explain your vote. Write an op-ed for your local paper. Post a statement online that doesn’t just rile people up but actually explains what happened and why it matters. That’s how you build trust. That’s how you lead.

That’s democracy.

Walking out? That’s just unplugging the mic and hoping someone clips the silence for social media.

And yeah, sometimes you still lose.

Sometimes you lose for two decades.

That’s part of the job. But the next election’s never far off. And if you’ve done the work, if you’ve shown up, stood your ground, and kept your integrity, you’ve earned the right to make your case again.

That’s the long game. The Madison game.

Show Up, Lose, Try Again

I didn’t run for office to play protest theater. I ran to govern.

That means showing up, when it’s boring, when it’s thankless, and especially when it’s easier not to.

Because the republic doesn’t survive on outrage. It survives on participation. On process. On people staying in the room long enough to lose a vote, make their case, and try again.

It’s not glamorous. It won’t make headlines. But it’s how the whole thing was designed to work.

And if enough of us still believe that, maybe we can keep the republic from collapsing under the weight of its own dramatic exits.