EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege” Oregon legislator and local dentist. Representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 9/1/25

EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege” Oregon legislator and local dentist. Representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 9/1/25

By State Representative Cyrus Javadi

One Lays Bricks. The Other Just Yells at the Wall.

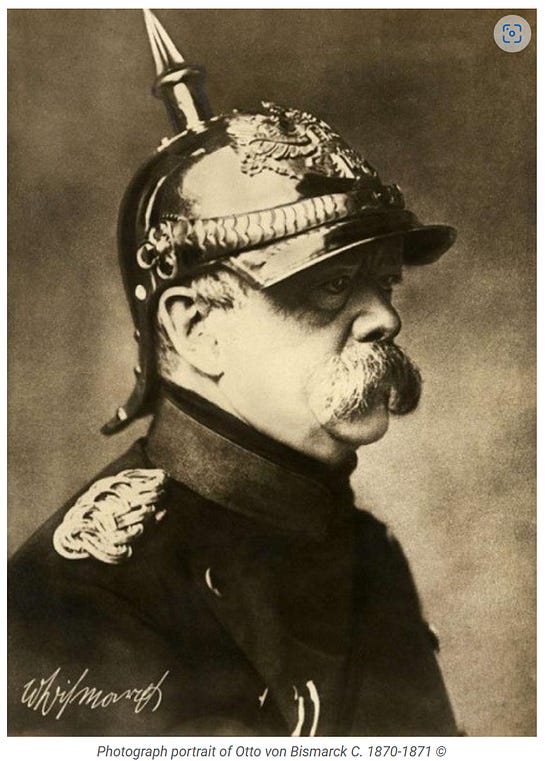

That guy in the photo is Otto von Bismarck, aka, the Iron Chancellor, political chess master, and the guy whose mustache could house a small family of birds. He is the guy who once said, “Politics is the art of the possible.”

He wasn’t being poetic. He was being brutally realistic.

You see, politics isn’t about utopias or purity. It’s about working with reality as it is: persuading, negotiating, compromising, and nudging the line of what’s achievable. It’s the slow grind that, over time, makes the impossible possible.

That line has stuck with me, because it’s the opposite of what so much of our politics has become. Too often, we’ve traded Bismarck’s “art of the possible” for the theater of the absurd. Instead of persuasion and trust-building, we get politicians performing for cable news soundbites, chasing clicks, and raising money off the latest outrage cycle.

And I’ll be honest: it’s the dislike for that kind of politics that moved me to run for office.

The Politics I Signed Up For

I didn’t get into politics to win a Fox News chyron or a CNN panel debate. That kind of politics might serve the egos of ambitious politicians, but it leaves everyone else battered around like ping-pong balls. One week you’re told to panic about this issue, the next week it’s another, and the whole time people are just trying to keep up.

The voices of ordinary people like neighbors working two jobs, small businesses fighting to stay open, families just trying to keep their heads above water, get drowned out in the noise.

That’s not why I ran.

I ran to find truth. To solve problems. To get government out of the way of my neighbor who shows up every day and works hard. To make sure those who stumble have a chance to get back up. And to stop government from steamrolling ordinary people in the interests of the powerful and well-connected.

When politics is done the way it’s supposed to be done, the way Bismarck meant when he called it the art of the possible, ordinary people actually stand a chance.

The irony is that the kind of politics that gets the least airtime is the kind that makes the most difference. The boring kind. The patient kind. The version that doesn’t chase headlines but builds trust.

It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t always look heroic. But over time, it moves the line of what’s possible.

Compromise Isn’t Cowardice

Our founding fathers understood this. The Constitution wasn’t handed down on stone tablets. It was hammered out in sweaty rooms, with men who disagreed on nearly everything finding just enough common ground to move forward.

The Great Compromise? Small states wanted equal power. Big states wanted power by population. So they created two chambers of Congress. Nobody got exactly what they wanted. But everybody got enough to keep the fledgling Republic alive.

And yes, some compromises, like those around slavery, were tragic and morally compromised. But without them, there might not have been a Constitution at all. Politics is often about navigating that tragic space where the urgent and the possible don’t quite line up.

Lincoln knew it too. He didn’t come into office demanding immediate abolition. He came in trying to preserve the Union, buying time, moving the line of what was possible until the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment could finally change the landscape forever.

That’s politics as the art of the possible: not pure, not perfect, but steady. Shaping the future in ways that stick.

What Happens When Politics Fails

While Reagan’s negotiations with Gorbachev moved history through trust, arms treaties, quiet diplomacy, and a commitment to finding common ground, China’s leaders took the opposite path. In 1989, students in Tiananmen Square asked for democracy. The answer came in tanks.

That’s the stark divide: one version of politics opens space for freedom. The other crushes it.

The Dark Side: Hitler and the Theater of Power

And then, of course, there’s Nazi Germany. The starkest warning of what happens when politics is reduced to performance and power.

Hitler didn’t practice the art of the possible. He practiced the art of manipulation, rage, and fear. He manufactured crises, demonized enemies, and burned down institutions until only his will remained.

I can’t reflect on that era without thinking of my own family. My grandparents had aunts, uncles, and parents who died in the events leading up to the Holocaust and in the Holocaust itself. They were victims of what happens when politics stops being about persuasion and compromise and instead becomes about spectacle and domination.

That wasn’t politics as the art of the possible. It was politics as the theater of the absurd and the horrific.

Where the only goal is power, and the only measure is obedience.

Today’s Theater, Tomorrow’s Price

Now, thankfully, we’re not living in 1930s Germany. But history doesn’t repeat itself, it rhymes. And today, too many have stopped using politics to solve problems, and started using it to build brands.

Instead of asking, “What can we actually achieve together?” the question has become, “What will get me the most clicks, the most donations, or the loudest applause at a rally?”

That’s not politics as art. That’s politics as reality TV. It’s a hamster wheel of outrage, where the goal isn’t to change anything but to look like you’re fighting. It can win you a news cycle, maybe even an election. But it doesn’t solve problems. It doesn’t fix roads, fund hospitals, or pass budgets. What does it do? It corrodes trust.

But real politics? Good politics? That kind builds credibility and opens doors.

Whereas, performative politics slams them shut.

Why It Matters Now

The irony is that the patient, incremental kind of politics actually changes the world. The performative version just leaves us exhausted.

Outrage politics can light up Twitter for a night. But it doesn’t build bridges, literally or metaphorically. It doesn’t win hearts and minds; it just entertains the already-converted.

The Berlin Wall came down because people practiced politics as the art of the possible. Nazi Germany rose because politics turned into theater for power. Tiananmen Square remains a scar because politics abandoned persuasion for force.

History isn’t subtle on this point.

When politics is practiced as persuasion, compromise, and the art of the possible, freedom expands.

When it is practiced as spectacle, fear, and the art of power, freedom contracts, and people die.

Two Paths, One Choice

Bismarck was right. Politics is the art of the possible. But the warning is just as important as the wisdom. Because there are two kinds of politics:

The steady, unglamorous kind that builds trust and moves the line of what’s achievable, even if it takes years.

And the toxic, performative kind that burns trust, shrinks the possible, and leaves us trapped in theater.

One brings down walls. The other builds them.

So the question we face today isn’t whether we like politics or not. The question is: which version are we willing to reward?

The art of the possible, or the theater of the absurd?

The Iron Chancellor called it the art of the possible. If we’ve had enough of the absurd, we can always choose a different script.

The choice is ours.