EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege.” Oregon legislator and local dentist, representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 2/2/26

Why the Places We Love to Visit Still Have to Pay the Bills but Can’t

No palm trees pretending it’s Malibu. No pastel boardwalks selling nostalgia by the funnel cake. Just cliffs, wind, gray water, and towns that look like they were built by people who fully expected to live there through winter.

Stay the night sometime. And it doesn’t really matter where (though I’ll confess a bias toward Tillamook County, Clatsop County, and the City of Clatskanie).

But seriously, anywhere you stay won’t disappoint. Cannon Beach. Manzanita. Gearhart. Depoe Bay. Yachats. Netarts. Names that literally sound like vacations because that’s what they’ve become. Each with its own tempo. Its own main street. Its own spot where the view makes you pull over even though you’ve seen it a hundred times and are now technically late.

Most of these towns are small. A few thousand full-time residents. Loggers. Fishermen. Farmers. Teachers. Retirees. Artists. Authors. Brewers. And, ahem, cheesemakers.

You won’t find many national hotel chains. But you will find family-run motels, short-term rentals, and boutique places that smell faintly like cedar and ocean air.

That’s the charm. You will feel like you are on the edge of the world. Untouched and unmasked. Raw and beautiful.

If Florida does polished, then Oregon does durable.

But here’s the thing about durability, like the polished, it requires upkeep.

And upkeep costs money.

The Part of the Brochure That Never Prints

Tourists see sunsets. Locals see sewer pipes.

Visitors admire the coastline. City managers stare at wastewater plants running at capacity in August and quietly calculate how many things have to go right for the next six weeks to not turn into a not so great headline.

That public restroom near the beach didn’t clean itself. The police officer directing traffic didn’t volunteer. The road you drove in on didn’t maintain itself. The water system didn’t upgrade itself because the views were nice.

In many coastal communities, a town of five or seven thousand residents can swell to thirty or forty thousand people on a summer weekend. On holiday weekends? More. Lots more. In places like Seaside (and really, almost everywhere on the coast) the population routinely quadruples during peak season.

Those extra people use the same roads. The same pipes. The same emergency services.

But, and this is an important but, they do not pay property taxes there.

This isn’t a moral complaint. No one is being accused of freeloading or bad intentions. It’s just math.

You cannot fund infrastructure for millions of visitors on a tax base built for a few thousand residents and then pretend optimism will cover the difference.

Optimism is not a revenue source.

The Visitor Who Pays Nothing (And Still Uses Everything)

Here’s the detail that almost never makes it into these conversations.

Most visitors don’t spend the night.

The data geeks who track these things—and yes, there are people whose entire professional lives revolve around counting cars, cell phones, and foot traffic—call them day-trippers.

They drive in from Portland, Salem, Eugene, Vancouver. They show up mid-morning, park wherever they can find space, use the bathrooms, walk the promenade, eat lunch, wander the beach, maybe grab ice cream, and head home before sunset.

They’re not doing anything wrong. They’re doing exactly what the coast invites them to do.

But they don’t pay a fee or a tax (unless they buy gas).

They don’t rent a room. They don’t book a short-term rental. They don’t show up on a hotel ledger.

They pay gas taxes elsewhere. They buy food and souvenirs ,which absolutely matters to the local economy, but the services they rely on most heavily are the ones funded by taxpayers.

Roads. Parking. Police. Fire. Emergency response. Water. Sewer. Public restrooms.

On a busy summer weekend, a town like Seaside may host tens of thousands of visitors, the majority of whom are not contributing a single dollar in tax that’s supposed to help support the community hosting them.

And that matters.

Because when we talk about how communities pay for tourism impacts, we’re already talking about a partial solution. Overnight visitors help. Day visitors don’t. Yet both depend on the same infrastructure.

And here’s the part that tends to get lost in legislative fine print: even the limited tourism dollars that do come in are largely locked away for advertising rather than the services day-trippers use most.

So the people who stay overnight pay a tax that mostly funds marketing, while the people who don’t stay overnight pay no tax at all—and both rely on roads, bathrooms, and emergency services that are quietly struggling to keep up.

Why “Just Raise Local Taxes” Isn’t Serious

When towns face this mismatch, they’re told to be creative.

Raise property taxes. Raise fees. Cut spending. “Live within your means.”

That advice sounds very responsible until you remember who’s actually using the services.

Raising property taxes means permanent residents pay more to serve temporary visitors. Cutting services means everyone gets less while demand goes up. And many local taxes require voter approval, which means asking year-round residents to vote themselves higher bills so someone else can enjoy the weekend.

As my friend in Texas likes to say, “That dog doesn’t hunt.”

Which is why local governments eventually turn to the one tax that actually matches usage.

Why the Transient Lodging Tax Made Sense

Now, enter the Transient Lodging Tax. I’ve talked about it before, but I think it’s good to do a micro-refresher for new readers.

The idea behind the lodging tax is simple. And fair.

If you stay overnight, you help pay for the place you’re staying in. You use more services. You generate real costs. You chip in.

Originally, local governments had broad discretion over how to spend that money. Roads. Police. Fire. Public restrooms. Marketing. Local choice.

That’s how it used to be. For decades. Then Oregon decided to get clever.

The 70 Percent Rule That Made Everything Backwards

In 2003, during a budget crisis, Oregon noticed it was funding statewide tourism promotion with Lottery dollars—money badly needed for schools, public safety, and healthcare.

Tourism was already struggling from the impacts of 9/11 and the dot.com bust. Hotel stays were down. Restaurants were struggling. Layoffs were everywhere. Tourism needed some love.

Enter Governor Kulongoski and the Oregon legislature. Many states in the country had a statewide transient lodging tax. A tax imposed on customers who spent the night at a hotel, motel, airbnb or campground. Funds collected from the tax were spent to support services tourists used while visiting. And, it could also be used to promote tourism from people abroad,

Perfect.

Except that the tourism folks were nervous about a tax being imposed on their service. They approached lawmakers with an idea.

Require that 80% of the funds collected with the tax be used on statewide tourism marketing instead of all going into the general fund.

Lawmakers liked the idea of investing in tourism believing it would create jobs, so they struck a deal.

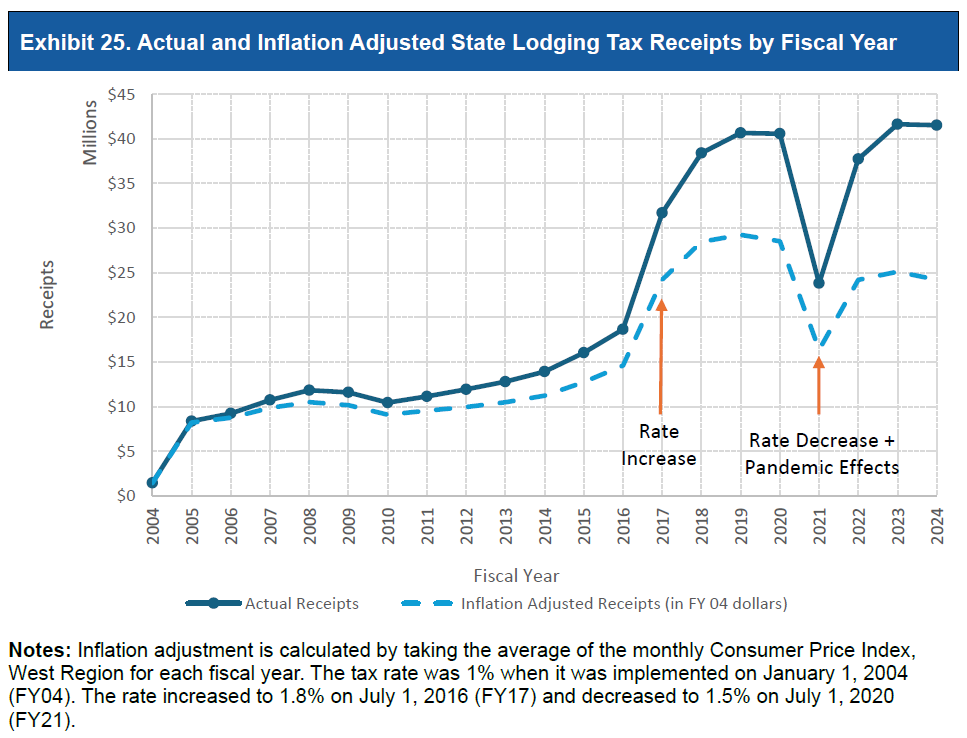

That part made sense. Sounds good. And it worked, really well. Tourism has increase consistently for the last 23 years (except for during the pandemic). And since 2016 it has more than doubled.

But here is something else the legislature did at the request of the lodging associations that doesn’t make sense. They imposed a rule on new local lodging taxes.

Why? Good question. On it’s face, for the same reason as the statewide tax. Their claim was “Hey, we are imposing a tax on ourselves, so we want the tax to mostly benefit us.”

So, for any new local TLT imposed after 2003: at least 70 percent must be spent on tourism promotion.

Not may. Must.

Let that sink in.

A tax paid entirely by visitors, collected by private businesses, imposed by local governments—yet largely earmarked for advertising and marketing rather than the services tourism depends on.

No other tax works this way.

Gas taxes don’t require 70 percent to promote gas stations. Sales taxes don’t bankroll retail ads. Utility fees don’t fund utility marketing.

In every other case, government collects the tax and decides how best to serve the public.

Except this one.

What This Bill Does (And What It Very Carefully Does Not Do)

So now we get to the bill—HB 4148.

This is the same bill we introduced during the long legislative session in 2025. No changes. Just more support.

Senators Weber and Nerron Misslin, along with Representative Julie Walters, myself and many lawmakers are sponsoring the bill.

Now, before anyone reaches for the fainting couch about a bill that raises taxes or ruins tourism, let’s be clear about what it doesn’t do.

It doesn’t eliminate tourism promotion.

It doesn’t raid marketing budgets.

It doesn’t punish hotels, short-term rentals, or the people who make their living welcoming visitors.

It doesn’t raise taxes. It doesn’t increase rates. And, it doesn’t create a new program or a new bureaucracy.

What it does (quietly, almost modestly) is restore balance.

Cities and counties would still be required to devote at least 40 percent of lodging tax revenue to tourism-related spending. That’s more guaranteed promotion than almost any other industry receives from a consumer tax. And, this is important, if a city or county wanted to invest 100% of the tax on tourism promotion, they absolutely can.

That’s the beauty of it. Cities and counties can decide how to meet the needs of their communities. Local governments could finally use the remaining funds for what tourism actually needs to function:

Infrastructure. Public safety. Emergency services. Basic livability. In other words, the stuff that makes visitors want to come back.

So, let me say it again:

No new tax. And no rate increase. Just permission to use existing dollars honestly.

And Yes, It Probably Should Go Further

Here’s the part that may make some people uncomfortable.

This bill is a step. A responsible one. A politically realistic one.

But it’s still a compromise.

There is no other industry in Oregon that receives a guaranteed share of a consumer tax for advertising, regardless of local conditions. None. Not agriculture. Not timber. Not manufacturing. Not tech.

Tourism is important. It deserves support.

But it is not so fragile that it requires permanent insulation from local decision-making.

If anything, the long-term conversation Oregon needs to have is whether it makes sense for the state to dictate spending ratios at all—or whether local communities should be trusted to balance promotion with the basic responsibilities of running a town.

But, this bill doesn’t settle that debate. For now, it simply nudges us back toward reality.

We Should Probably Make Sure the Towns Work

People don’t visit Oregon because of ads alone. They come because the place feels real.

Livable. Human. Cared for.

If we want it to stay that way, we should probably make sure the towns behind the views still work.

Because, pretty coastlines are important. But, functioning communities are essential.