EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s an installment from Tillamook County’s State Representative Cyrus Javadi’s Substack blog, “A Point of Personal Privilege.” Oregon legislator and local dentist. Representing District 32, a focus on practical policies and community well-being. This space offers insights on state issues, reflections on leadership, and stories from the Oregon coast, fostering thoughtful dialogue. Posted on Substack, 12/9/25

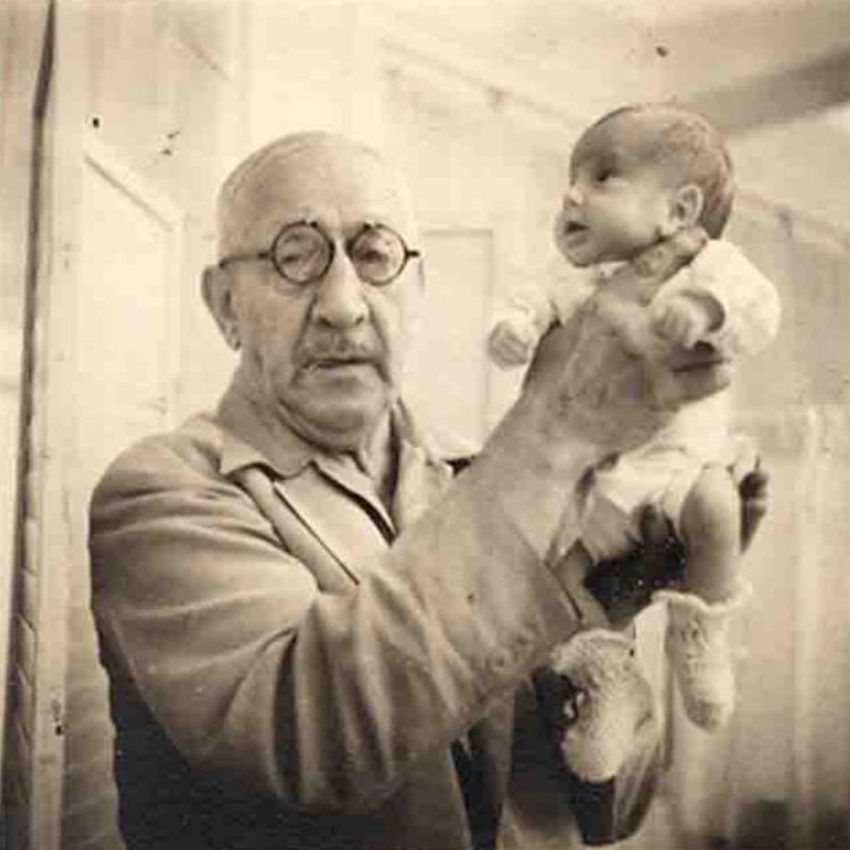

What a century-old carnival act can teach us about the quiet collapse of rural healthcare in Oregon

Yes, you read that right.

Why? Well, partly because the incubator was new and miraculous. But partly because someone had to pay for it. Hospitals weren’t buying $1,000 machines for babies nobody thought would survive anyway, so a doctor built a boardwalk attraction to fund neonatal care.

Today, we don’t charge admission to see preemies. But hospitals still rely on strange, awkward, Rube Goldberg–level financial contraptions to keep care available. What used to be a literal carnival act is now an accounting one.

And if you want to understand that, you have to walk into a part of the hospital patients never see: the back office.

Not the clinical area. Not the hallway with the crash carts. I mean the fluorescent back-office labyrinth where printers jam out of spite, where the finance director keeps a whiteboard of numbers written in dry-erase hieroglyphics, and where someone has been working at a “temporary” desk since the Bush administration.

It’s where administrators ask the questions no one wants to ask out loud:

Can we hire another night nurse?

Can we keep labor and delivery open?

Can we replace the CT tube before it dies like an old water heater?

How long can we keep treating Medicaid patients before the entire place sinks?

Patients don’t see these conversations. But the health of the system depends on them.

And that brings me to Coos Bay.

Welcome to the Back Office of Oregon

A few months ago, I traveled down to Coos Bay, Oregon for an economic summit. It’s beautiful there. Think mist rolling over the evergreens, clean Pacific air, and enough scenery to make you wonder why you ever considered paying rent in Hillsboro.

Coos Bay was once a timber powerhouse. The high school had thousands of kids. Families built their lives around the mills. Movie stars vacationed on the lakes. Then federal policy, lawsuits, and decades of regulatory decisions shrank the industry, and with it the local economy.

But some things are turning around. New investments, new industries, a little optimism.

So while I was in town, Bay Area Hospital invited me and a few other legislators over.

The reason was not subtle. They’re failing. Fast.

And not failing in the “revenues were a little light this quarter” sense. Failing in the “the structure of American healthcare has been quietly eroding under our feet for decades” sense.

They laid the numbers out like a coroner presenting a autopsy.

In 2022, the hospital lost $61 million.

The next year: still in the red.

2024: they defaulted on a $47 million loan.

This last year: another $24 million loss.

These aren’t rough patches. These are “turn off the lights when you leave” numbers.

Bay Area Hospital has 172 beds. It’s the only Level III trauma center on the entire south coast. Its service area—Coos, Curry, and Douglas Counties—is bigger than New Jersey. If it closes, the nearest cardiologist is in Eugene, which for many south coast residents is a five hour drive. Each way.

Inconvenient? More like catastrophic.

So what’s happening?

The Math Finally Revolted

Their payer mix told the story. More than half their patients are on Medicare or Medicaid, both of which reimburse below the cost of care. Commercial insurance used to patch the hole, but rural Oregon doesn’t have enough commercial payers to keep patching anything.

When payroll jumps 25% in four years and revenue barely inches 5%, the math doesn’t bend. It snaps.

And labor is only the first domino.

For the past five years, everything has gotten more expensive.

Contract nurses during COVID cost hospitals $150–$200 an hour. And those rates didn’t magically drop when the pandemic waned. Respiratory therapists, radiology techs, behavioral health specialists, and literally everyone in the industry costs more because scarcity costs more. Oregon spent years trying to emulate the healthcare workforce of California without remembering that California has… well, a lot more people.

Then come drug costs, which have taken on a life of their own.

Specialty drugs like biologics, cancer therapies, and autoimmune treatments are now their own economy. Tocilizumab (I can’t pronounce it either) runs $7,000–$8,000 a dose. Keytruda can hit $13,000 a dose. Rural hospitals cannot negotiate the bulk discounts big systems get, so the same medication punches a much bigger hole in the budget.

Take ten oncology patients (just ten) and you’ve crossed the million-dollar mark before anyone has even printed the discharge instructions. Reimbursement will not cover it. Not close.

But unlike elective procedures, chemo isn’t something you can “defer.” A hospital can’t say, “Sorry, we don’t stock the drug that keeps you alive. Try again on Tuesday.”

So imagine taking your wife, your partner for three decades, to the ER because something feels off. The scan shows cancer. Your world shifts. But then the hospital tells you the medication she needs isn’t available because the budget couldn’t absorb it. Sorry.

At that point, it’s not the cancer that failed you. It’s the system.

And then there’s the technology, because modern medicine needs hardware that makes NASA jealous.

Replacing a CT tube can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Electronic health records like the Epic EHR system in Bay Area Hospital’s case, require multimillion-dollar loans, cybersecurity teams, IT staff, ongoing licensing fees, and the patience of Job.

But once you sign the loan, the bank expects repayment even when your operating margin crawls below zero. Incredible, I know.

EHRs are wonderful clinically. They’re also expensive in an out-of-this-world kind of way.

We don’t like to say it out loud, but hospitals are no longer just hospitals. They’re IT departments with operating rooms attached.

So, how much does it cost to run a hospital in 2025?

More than anyone wants to admit. And more than the system was built to handle.

The National Problem Hiding in a Local Story

The hard truth is that Bay Area Hospital is not an outlier. More than half of rural hospitals nationwide are at risk of closure. Margins since 2022 have hovered near zero. Many facilities are operating at losses year after year, holding the line mostly through grit and denial.

When government payers reimburse below cost, commercial insurance makes up the difference. But commercial coverage is shrinking as the population ages and employer coverage declines.

This is not a moral problem. It’s not ideological. It’s a structural mismatch between the cost of modern medicine and the way we pay for it.

We built a 21st-century clinical system on top of a 20th-century financing model and hoped no one would notice the foundation cracking.

Bay Area Hospital didn’t fail because someone forgot how to run a hospital. It’s failing because the cost of being a hospital finally outran the story we tell ourselves about how healthcare works.

America loves to imagine healthcare as a combination of heroic doctors, grateful patients, and pharmaceutical ads where someone frolics in a meadow while listing side effects like “may cause your head to fall off.”

But the back office is where the real story lives.

It’s where people stay late arguing over staffing models.

It’s where someone tries to find room in the budget for drugs that cost more per dose than a used Mercedes.

It’s where a broken CT tube becomes a crisis.

It’s where Medicaid reimbursement determines whether labor and delivery stays open.

And it’s where, sooner or later, the numbers stop cooperating.

The Uncomfortable Lesson of the Infantorium

Which brings me back to the premature babies in St. Louis.

The incubator exhibit was a workaround. An awkward, ethically questionable workaround. Because the system of the time wasn’t built to support the care that medicine had suddenly made possible.

In other words: the science moved faster than the financing model.

Sound familiar?

Today’s incubators aren’t sideshow attractions. They’re multimillion-dollar buildings filled with people trying to keep a service running that we all rely on but we don’t really know how to pay for.

We may recoil at the Infantorium (and we definitely should), but the truth is, hospitals are still trying to improvise their way out of a structural mismatch. They’re just doing it with spreadsheets rather than carnival barkers.

Bay Area Hospital isn’t sinking because of incompetence. It’s sinking because we’re still pretending the old math can fund the new medicine.

And the back office knows it.