By Butch Freedman

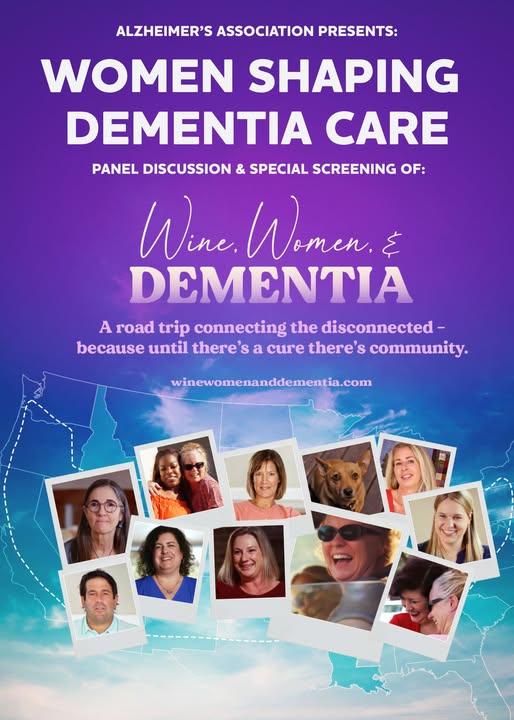

Yesterday I attended a viewing of a documentary film about caring for loved ones who are suffering through the final stages of dementia. It was an honest and loving look inside the pain and often-times joys of being a caretaker for the spouses, parents, and others who are slowly losing their mental and physical capacities. The title of the film (available to stream on PBS Online) is “Wine, Women, and Dementia.” The documentary evolved from a blog kept by Kitty Norton, the producer of the film. She describes her own experience of caring for her mother through all the steps of dementia up till her death, during which time she was contacted by many other folks around the country who described their own struggles. After her mother passed away, Kitty set out on a cross-country road trip to visit and speak with some of the people who were dealing with the same caretaking issues at end-of life. The film was tender, funny, and heart-breaking. I’d recommend it to anyone who has concerns about how to deal with the issue of dementia—or the possibility of having to make those decisions about your own life or those close to you.

As much as I was impressed with how the people shown in this film handled their various situations, I was left feeling that some piece was left unsaid. Namely, that there are other options besides deciding to take on this often long and painful process of seeing dementia through to its inevitable end. As the film makes clear—dementia is not curable.

In my own family there is a history of dementia. I have vivid memories of visiting my grandmother in what passed for a nursing home. It was frightening to my then-young mind, both to see this prison-like building and to visit with my grandmother who no longer looked or spoke like the woman I had revered. My father died in his early 70’s from illnesses associated with Alzheimer’s. In a way, I think he was lucky not having to struggle on for years, each harder than the next. Some of my family are even now struggling with the ravages of old age on their mental well-being. All of which has convinced me that if and when I find myself in a position where I am no longer able to function on my own and the prognosis is further degradation and inability to have any sense of personhood, I will make every effort to go out gracefully on my own terms. Well, how do you manage that you may correctly ask. It’s not easy, but it is doable, if you have the right information and availability and most importantly, make your wishes known to those who will be there with you in the end. My wife and I have discussed what we want to do — which is, to be blunt, to end our own lives when we see fit and go out with a smile.

In more enlightened countries, (i.e. Switzerland) arrangements can be made to experience a gentle, supervised by physicians, death, surrounded by loved ones if you so choose. Oregon has a “death with dignity” law, but it is limited and requires two doctors to certify that the sufferer has only 6 months to live. That is largely impossible in the case of dementia related issues. What many people choose to do is to voluntarily (of course) stop eating and drinking. I’m told that regime is not as foreboding as it sounds, and can actually resolve into a state that is quiet and peaceful.

It’s always going to be a difficult choice — these end of life decisions, but it is important I believe to realize there are options. It’s your life and your death and you can and should be in charge of how it plays out.

For further reading see:

•Advice for Future Corpses (and those who love them) by Sallie Tisdale

•In Love, a Memoir of Love and Loss by Amy Bloom

•Finish Strong: Putting Your Priorities First at Life’s End by Barbara Coombs Lee