By Denise Donohue

I remember a Tuesday afternoon that smelled like pencil shavings, cafeteria pizza, and desert dust blowing in from the Las Vegas heat. My office sat right next to the boys’ bathroom, which meant I heard everything. Every locker slam. Every whispered insult. Every burst of commotion that started with laughter and ended in silence.

My office itself was… let’s call it lived in. My desk was chronically a mess. Papers stacked in what I insisted were very organized piles. It was only clean once a year, and that was during summer break when no one was around to witness the miracle.

But in the corner sat the real treasure. A big, oversized, slightly worn chair that I am fairly certain I rescued from the side of the road. It became the unofficial safe haven of the school. Kids curled into it. Teachers sat in it. And if we are being honest, there may have been a few educators who shut the door and took a five minute nap in that chair. Do not tell the boss.

That was the chair he sank into that day.

He had just been shoved into the bathroom wall right next door. The noise had traveled straight through the thin office walls, as it always did. A scuffle. A thud. A door slamming. Then the sound I hated most. Laughter fading down the hallway.

He walked in trying very hard not to cry. Shoulders squared like a soldier. Jaw tight. Eyes glassy but determined. He sat down and said, “It’s fine.”

Which in middle school language means it is absolutely not fine.

When I gently asked what hurt the most, he surprised me. It was not the shove. Not even the names. It was this:

“Everyone just watched.”

Everyone just watched.

Now here is the part people do not like to talk about. When I later met with the boy who did the shoving, he was not some movie villain twirling a mustache. He was anxious. Angry. Sleep deprived. His home life was chaos. He had learned that power is the fastest way to stop feeling small. Hurt people hurt people is not a Hallmark quote. It is clinical reality.

So we had three mental health stories unfolding at once.

The bullied child was internalizing shame, developing hypervigilance, and starting to believe the lie that he deserved it.

The bully was rehearsing aggression as a coping skill and wiring his brain to associate dominance with relief.

And the bystanders were absorbing a lesson about safety. They were learning that staying quiet keeps you protected. They were also learning that cruelty can go unchecked.

In school counseling we talked often about the bystander effect. Research consistently showed that the person with the most power in a bullying situation was not the adult, and not even the bully. It was the peer who said, “Hey. Not cool.” Or the one who walked over and stood beside the targeted child. The one who disrupted the script.

When a bystander speaks up, even briefly, the bullying decreases. Not always dramatically. Not always instantly. But measurably. Because environments shape behavior. Silence shapes it too.

Now zoom out to what’s happening now.

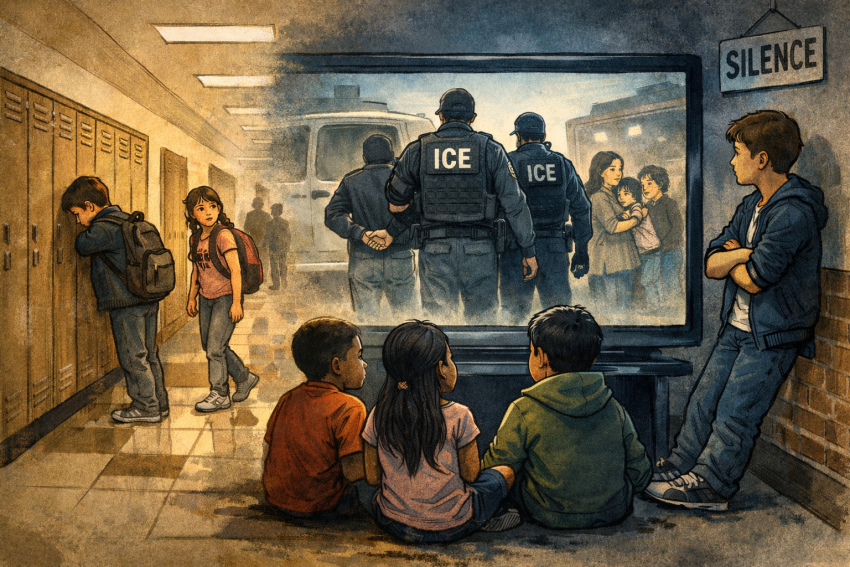

Our children are watching something much bigger than a middle school hallway.

They are seeing images on the news of agents from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement arriving in neighborhoods. They are seeing families in distress. They are hearing adults argue loudly about who deserves what and who belongs where. Some children feel fear. Some feel anger. Some feel confused. Some absorb rhetoric that hardens into contempt. But none of them are unaffected.

Even the ones who look like they are not paying attention.

The nervous system does not require a front row seat. It only requires exposure.

When children repeatedly see images of authority figures taking parents away, or people being detained, or communities in chaos, their brains do what brains are designed to do. They scan for threat. They ask, Am I safe? Is my family safe? Is this how power works? Is this how we treat people?

For some children, especially those from immigrant families, the fear is personal. For others, it is ambient. But ambient stress still alters a developing brain. Chronic exposure to fear based messaging can increase anxiety, aggression, or emotional numbing. And emotional numbing might be the most dangerous of all. It is the bystander reflex on a national scale.

Then there are the children who absorb something else. They see force. They see division. They see adults cheering or mocking. And they learn. They learn who to stand with. They learn who to stand against. They learn that the loudest voice wins. If we are not careful, they may also learn that empathy is optional.

We cannot pretend our youth are insulated from this. They carry phones. They overhear conversations. They sit in classrooms with peers whose families are directly impacted. They see the tension in their parents’ shoulders. Children are excellent observers. They are just terrible at paying taxes.

And here is the uncomfortable parallel.

In that middle school hallway, the child who was bullied suffered. The bully suffered. But the bystanders were the tipping point.

In our broader community, there are children who feel targeted. There are adults acting with force. There are systems at play. And then there are the bystanders. The rest of us. The ones who watch the footage, scroll past it, shake our heads, or say nothing.

Silence is a lesson.

It teaches our children that fear is normal. That cruelty is tolerable. That discomfort should be avoided. That speaking up is risky.

But involvement is also a lesson.

It teaches them that civic engagement is part of adulthood. That protecting the vulnerable is not weakness. That disagreement does not require dehumanization. That communities are built, not just inherited.

I am not suggesting that everyone needs a megaphone. I am suggesting that our youth are watching how we respond. Are we modeling thoughtful dialogue? Are we asking hard questions? Are we advocating for due process and human dignity? Are we showing up in ways that are lawful, respectful, and courageous?

Because the bystander has always had the most influence.

Back in that school hallway, it was not the principal’s speech that changed things. It was one student who rolled his eyes at the bully and said, “Dude. Stop.” It was another who walked the targeted boy to class. It was the subtle but powerful shift of the crowd.

Everything quieted after that.

Our kids do not need perfection from us. They need participation. They need to see adults who refuse to be passive in the face of harm, and who refuse to become hateful in the face of disagreement. They need to see that strength can look like compassion. That courage can look like standing beside someone.

Childhood should be about bike rides, awkward dances, and arguing over whose turn it is on the game controller. Not about wondering if families will be torn apart.

If environments shape children, then we are the environment.

The question is not whether our youth are being impacted. They are.

The question is what lesson they are learning from us while they watch.

https://www.tillamookcountypioneer.net/new-weekly-advice-column-conversations-with-coach-denise/

Let’s Talk – send your questions to Coach Denise – editor@tillamookcountypioneer.net

www.optimallifecoachingforteens.com