By Cara Mico

A long trend of the past two centuries has seen rural areas shrink as people move to areas of greater economic opportunity. Economic cycles see recessions when US gross domestic product declines for two successive quarters, which happened in quarter two of this year.

A recession is a major economic issue, and officially we’re in one, at least by one metric.

The truth is that it’s a subjective term, and, as always, the truth lies in the bigger picture; 2.7 million jobs were added in the first two quarters of 2020, the housing supply is at historical lows and real estate prices are at historical highs, and the unemployment rates are at a 40 year low. These metrics taken on their own suggest that the economy is healthy.

But it’s difficult to look to history during unprecedented times coming from climate instability, multiple unexpected and looming wars, and severe global health crises.

Economists also consider wages, inflation, household debts, and the increasingly rising cost of housing.

So let’s look at the first two metrics individually and then evaluate how economists consider their interaction. (Housing and debt cycles are bigger issues and we’ll try to tackle that in follow up articles.)

First let’s consider real wages. Since the inception of the federal minimum wage in 1938, congress has increased the minimum hourly rate workers make nine times, most recently in 2007/9. The rate was strongly linked to worker productivity for the first 30 years.

Since 1979, productivity increased 60% while median pay is only up 16%. Coupled with inflation the purchasing power of the dollar has sharply declined in the same time period (see graph below).

This essentially means that while a dollar is worth more, the value hasn’t kept up with the cost of goods.

This is connected to a variety of factors. Productivity is tied largely to technological innovation and the advent of the internet. This means that workers in these industries profited more while those in other industries such as service workers and agriculture saw little to no increase in wages. In short many blue collar workers were left behind while more white collar workers gained economic status.

These two tiers of workers experience recessions differently. There isn’t one economy. There are many interrelated economies, some of which experience economic downturns more heavily than others.

Now let’s look at the bottom of the wage category. The minimum wage has not kept up with inflation and purchasing power. Economists for at least a decade have suggested that were this pegged to inflation, the minimum wage would be closer to $23. This is nothing compared to one analysis that found if minimum wages kept pace with corporate bonuses, prevailing wages would be over $60 hourly.

The reasons for not increasing the minimum wage are largely tied to the burden this would place on sole proprietors and small businesses. Almost half of all US workers are employed by a small business.

Some argue that to nearly triple the prevailing wage for half of all workers would cause economic instability, although this has been debated by many.

This is why congress is considering a staggered wage increase to $15/hour over five years but even this has been met with push back. By comparison, the 1,000,000 people in the top 1% in the US make $500,000 or more annually. This of course varies by state.

A recession for the 100,000,000 people at the bottom means something very different than for those at the very top. Especially in a time when most people would struggle to come up with $500 for an emergency, despite working multiple jobs. (We aren’t going to look at the unemployment rate in this article either, it’s too complex a topic to tackle as a sidenote. Generally the real unemployment rate is obscured by the long-term unemployed, the underemployed, those working multiple or under-the-table jobs, and those who gave up looking for work.)

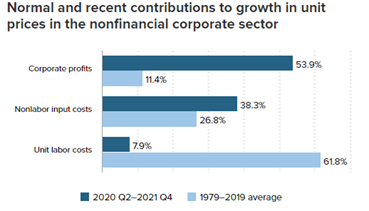

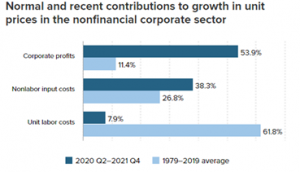

It’s something else altogether for corporate shareholders for companies which have seen record profits from shortage related price hikes (see graph at left).

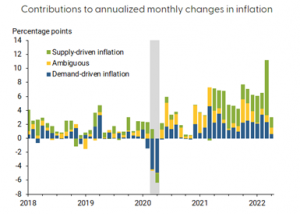

One economic analysis looked at inflation from both supply side and demand. They found that recent inflation is largely driven by supply side shortages, largely related to labor shortages from the pandemic (see graph at left).

Another study found that most of the inflation, which rose faster than anytime since 1981, we’re experiencing now are being driven by record corporate profits (see graph below).

The graphs taken in conjunction show that corporate America has profited more in the last two years than in the last 10.

So when those in Washington DC say the US isn’t in a recession, they’re not talking about the impact of inflation and supply shortages on the average worker, they’re looking at gross corporate profits. Even though unemployment rate has fallen from 3.9% to 3.6%, many are still struggling and spending less, which will have major lasting impacts. Large companies are also cutting positions despite earnings.

How long the recession will last is up for debate with some analysts suggesting it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy and other outlooks predicting that a long-term recession is inevitable, or perhaps a soft-landing recession is in our future. Economists are also predicting a global recession as well since pre-pandemic 2019.