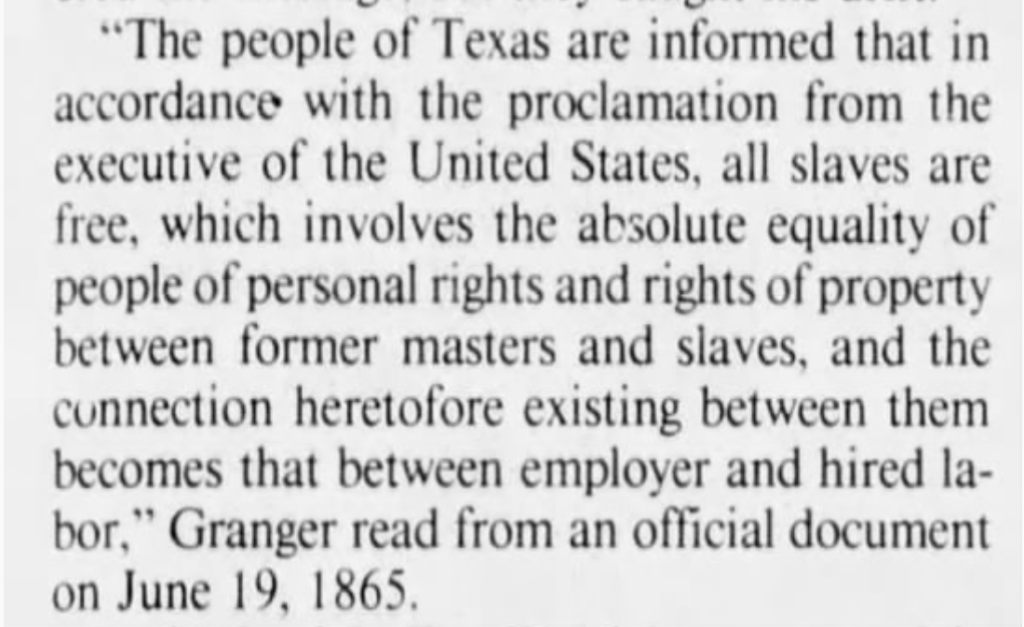

When the war ended on April 9, 1865, Union troops made their way through the Confederate States, reclaiming them and announcing emancipation for the enslaved. Union General Gordon Granger was given command of the District of Texas, and in June 1865, he boarded a steamer at New Orleans bound for Galveston. He arrived on June 18, and his first order of business the following morning was to read aloud General Order Number 3. As Gen. Granger began, a crowd gathered in the streets, “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free….” The crowd erupted with cheers, and a spontaneous celebration spread across the city and state.

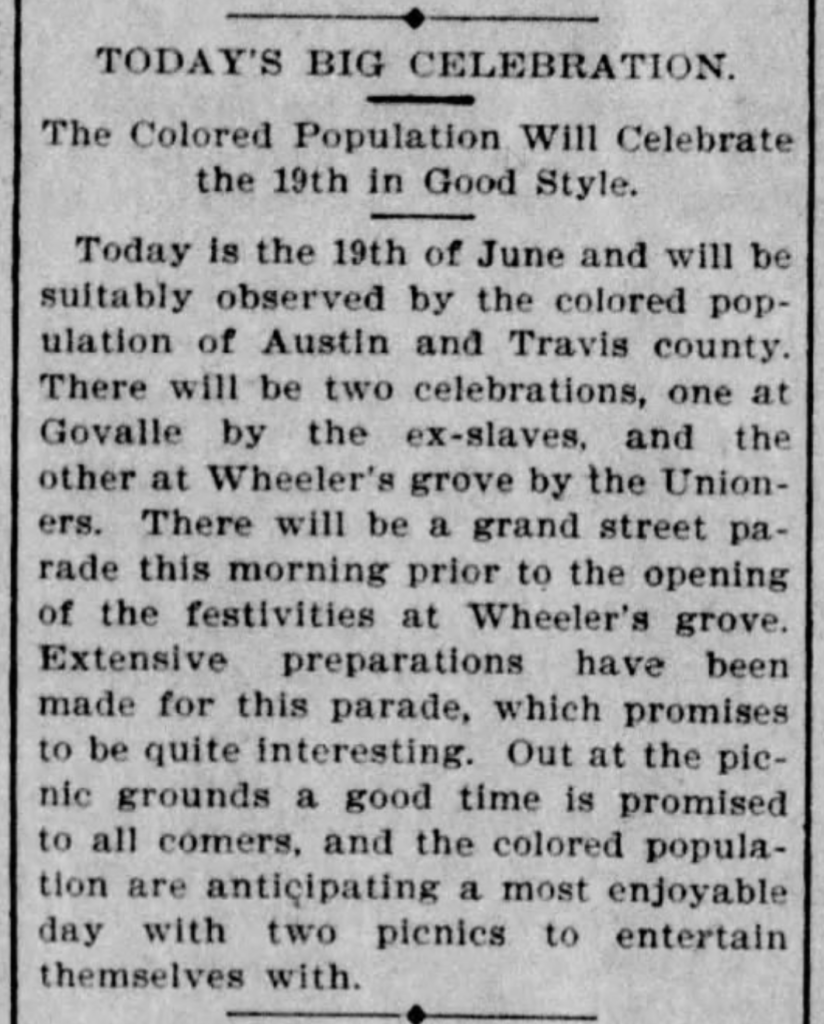

In the following years, June 19 marked that historic occasion, and Texas celebrated the date as Emancipation Day. It later came to be known as Juneteenth. Though first celebrated primarily in Texas, the celebration gained momentum and moved to other states. In 1872, on the seventh anniversary of Emancipation Day, some 2000 Black citizens from Columbus, Texas, formed a procession through the town for a Juneteenth celebration. By 1883, the crowd gathered in Corsicana, Texas, numbered more than 5,000. By 1900, Juneteenth had become an unofficial holiday in Texas.

During the mid-1900s, Juneteenth celebrations shifted from larger public celebrations to more informal private gatherings. A renewed interest in Juneteenth in the late 1970s led Texas to become the first state to recognize June 19 as an official state holiday. Following suit, in 1997, Congress passed a resolution officially recognizing Juneteenth. The fight to recognize Juneteenth on a national level culminated in 2021 when President Biden signed the bill declaring June 19 a federal holiday.